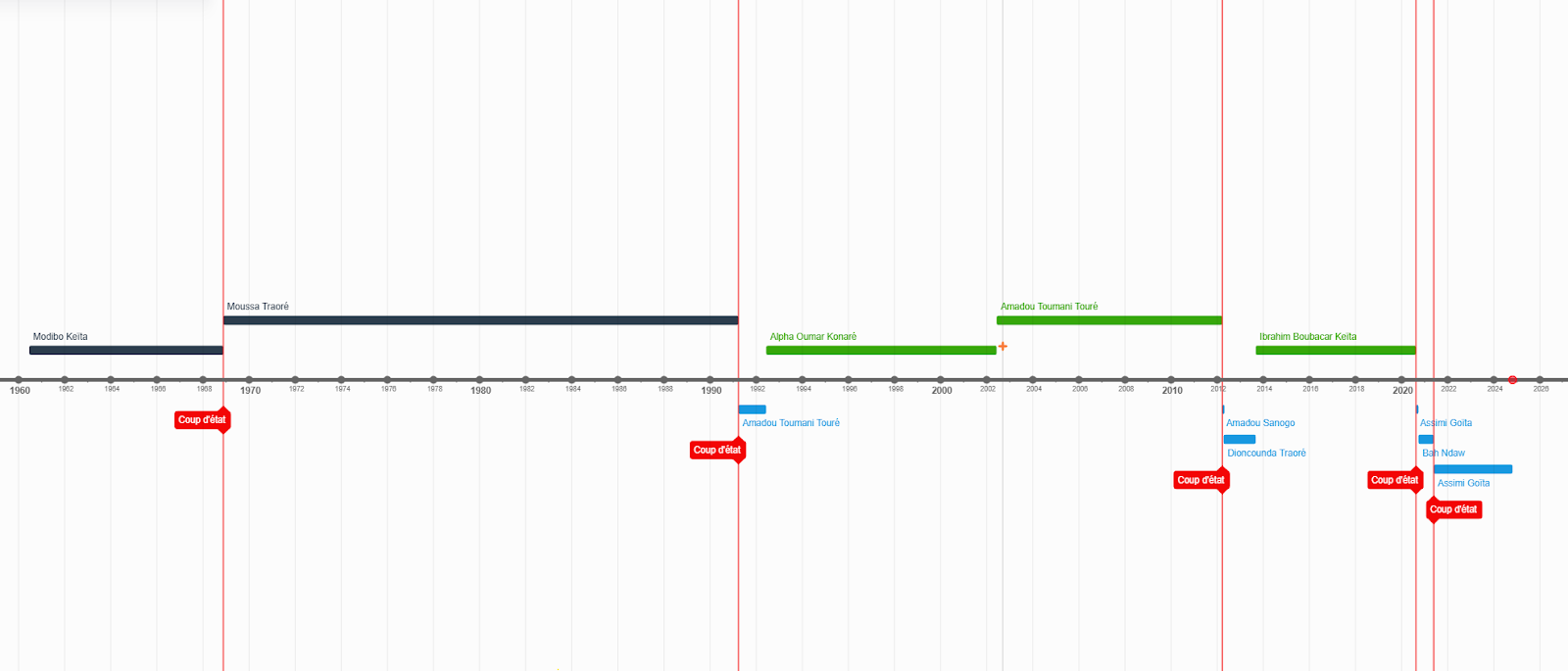

From Independence to Instability: Mali's Leadership Journey

A Historical Overview of Mali's Presidents, Coups, and the Struggle for Stability.

This article marks the beginning of a series on Mali, offering a historical lens to understand the West African nation's complex political evolution and current challenges. As in the previous analysis of Sudanese coups, I aim to trace Mali's journey through dictatorship, democracy, and coups - including two in just the last five years.

In 1960, the French colonial territories of Senegal and French Sudan (Mali) declared independence as the unified Mali Federation. At the time, Senegal’s Leopold Sedar Senghor was the leader of the new Federal Assembly, and Mali’s Modibo Keïta was the interim President until elections could be held later in the year.

Before the elections could be held, Senegal left the union and declared independence from the federation due to rising tensions over governance, power-sharing, and the federation's structure.

The Republic of Mali then declared independence and Modibo Keïta became its first President. Not long after taking office Keïta consolidated his power and made Mali a one-party state.

Initially, he distanced Mali from its former coloniser and aligned closer with the Eastern Bloc. However, this action was ultimately reversed due to the severe negative economic impact of trying to transition the economy which was already so closely tied to France.

In 1966, Keïta expanded his powers and suspended the constitution in an attempt to hold onto power. The economy continued to struggle and two years later, eight years into Mali’s independence and Keïta’s premiership, a military coup was carried out by junior officers of the Army. Keïta was arrested and one of the coup leaders, Moussa Traoré, took over as chairman of a transitional Military Committee.

Moussa Traoré initially promised democratic elections to select the next President, these did not materialise and he continued as chairman and the defacto head of state for eleven years. Following a referendum, Presidential elections were first held in 1979 under a new constitution introduced with the intention of transitioning to civil democratic rule to replace the decade of military leadership. In the first election, Traoré ran unopposed due to there being no other legal parties and was elected to his first six-year term as President with 99% of the vote

At the end of his first term, Traoré won re-election, once again running unopposed, securing a further six years. Near the end of Traoré’s second and final legal term, multiple political parties were set up across the country in an attempt to introduce multi-party elections. However, Traoré violently suppressed the new democratic movement and pro-democracy rallies. In one case, an estimated 150 protesters were killed at a single march in the capital. As a result of the violence and in an act of support for the demonstrations, Traoré was arrested by the commander of his Presidential Guard Amadou Touré.

Amadou Touré took the chairmanship of an interim military government set up to oversee the creation of a new constitution and to establish a true, multi-party democratic election process.

In what is sadly a rare move by an interim leader after a coup, Touré remained leader for just one year during which elections were set up and held before he peacefully handed over power to the first democratically elected President of Mali, Alpha Konaré.

Alpha Konaré served as President of Mali for two successive five-year terms between 1992 and 2002, the maximum allowed under the new constitution. Konaré peacefully stepped down at the end of his second term and power was transferred to the next elected President Amadou Touré, the former chairman of the previous interim military government. Alpha Konaré has the unique achievement of being the only Malian President to reach the end of his term.

Amadou Touré retired from the Armed Forces in 2001 to allow him to stand in the 2002 election. Touré then successfully stood for re-election in 2007. During his Presidency, regional shifts such as the rise of jihadism and the overthrow of Libyan President Gaddafi led to conflict in the north. The Tuareg peoples ignited a fight for their independence from Mali under a new state known as Azawad. Jihadist groups, primarily Ansar Dine, also began taking control of areas in the north at the same time.

In the run-up to the 2012 election Touré confirmed that, in accordance with the constitution, he would not stand for a third term. Discontent had been growing in the Armed forces due to the failure to effectively control both the Tuareg rebellion and the rise of Ansar Dine. The death of more than 80 soldiers in a single attack at Aguel Hoc in the east led to protests from the troops. Just months before the end of his Presidency a coup was carried out by the Malian Armed Forces during a visit by the Minister of Defence to an Army barracks.

Amadou Sanogo, the leader of the coup, assumed control as Chairperson of a transitional committee and suspended the constitution.

ECOWAS quickly implemented sanctions, froze assets, and closed borders to Mali. After brief negotiations, and just 21 days in power, Sanogo ceded control to Dioncounda Traoré as interim President until democratic elections could be held. Traoré was an ally of the deposed Touré and had supported both his 2002 and 2007 election campaigns.

The Tuareg forces in the north had increased the rate of their advances during the chaos of the coup and short rule of Sanogo, taking several more towns and military bases. After Dioncounda Traoré took power, he took a strong stance against the Azawad independence campaign, demanding that it give up control of the territory it had secured.

Democratic elections were held in late 2013 and power was handed over from Traoré to the newly elected, Ibrahim Keïta.

Ibrahim Keïta had previously stood for Presidential elections in 2002 and 2007, losing out on both occasions to Touré. In contrast to the initial stance of interim President Traoré before him, Keïta’s approach to the Azawad rebellion was to pursue a peaceful resolution allowing the focus of combat resources instead on the Jihadist insurgencies. The Keïta government negotiated a ceasefire with the Azawad rebels in mid-2013. however, by the end of the year, the rebels ended the ceasefire citing Malian army attacks against protestors as justification for renewing operations.

French forces were invited into the country in 2013 to assist in halting and reversing the gains made by jihadists in the North. At the time there was overwhelming support from the Malian population for French intervention. The operations were a resounding success with the cities and territory taken by Ansar Dine returned to government control in just a few months. The UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was established to provide peacekeeping and help to ensure stability in the north. After the success of the operation, the French were invited to remain in the country as a part of the newly created Operation Barkhane. Barkhane was set up to expand on the Mali operation and deal with jihadists in the wider Sahel region. It was created in coordination with the “G5 Sahel” comprised of Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger.

Although Keïta was reelected for a second term in 2018, tensions had been rising between the government and elements of the Malian armed forces, unhappy with the continued deployment of French forces across the country despite the jihadists largely being defeated. In 2020, a coup was carried out by members of the Malian Armed Forces. Keïta was detained by the putschists, quickly resigned, and dissolved parliament in an attempt to prevent any divided loyalties in the army from leading to bloodshed.

Assimi Goïta was one of the leaders of the coup against Keïta and initially led the transitional committee established in part to initiate elections for a new President. Goïta led for just one month before Bah Ndaw, a civilian and the former Minister of Defence, was chosen by the committee as interim President with Goïta to serve instead as his Vice President until the elections were held. Ndaw was chosen by the committee under external pressures from ECOWAS for civilian rule to be maintained throughout the transition.

Bah Ndaw served as interim President for just eight months before Goïta carried out a second coup and Ndaw was arrested on accusation of attempting to prevent a transfer back to a democratic process.

Assimi Goïta was subsequently declared interim President of Mali by the constitutional court in mid-2021 and vowed to hold elections the following year. No election was held and Goïta remains in power to this day as "interim President".

Since taking power, Goïta has expelled both the MINUSMA task force and the French Armed Forces. To support the Malian Armed Forces in their campaign against the Tuareg and Jihadist elements still active in the country, he instead invited Russia's Wagner mercenary force into the country.

Mali's journey since independence has been defined by a complex interplay of democracy, authoritarian rule, and military intervention—shaped by both internal pressures and regional dynamics. Understanding this turbulent leadership history provides an essential context for grasping the country's current political and security challenges.

Stay tuned for the next article in the series, where we will explore the origins of the Tuareg rebellion and the presence of Azawad separatism, a pivotal aspect of Mali’s past and key to its future.